Understanding Pain

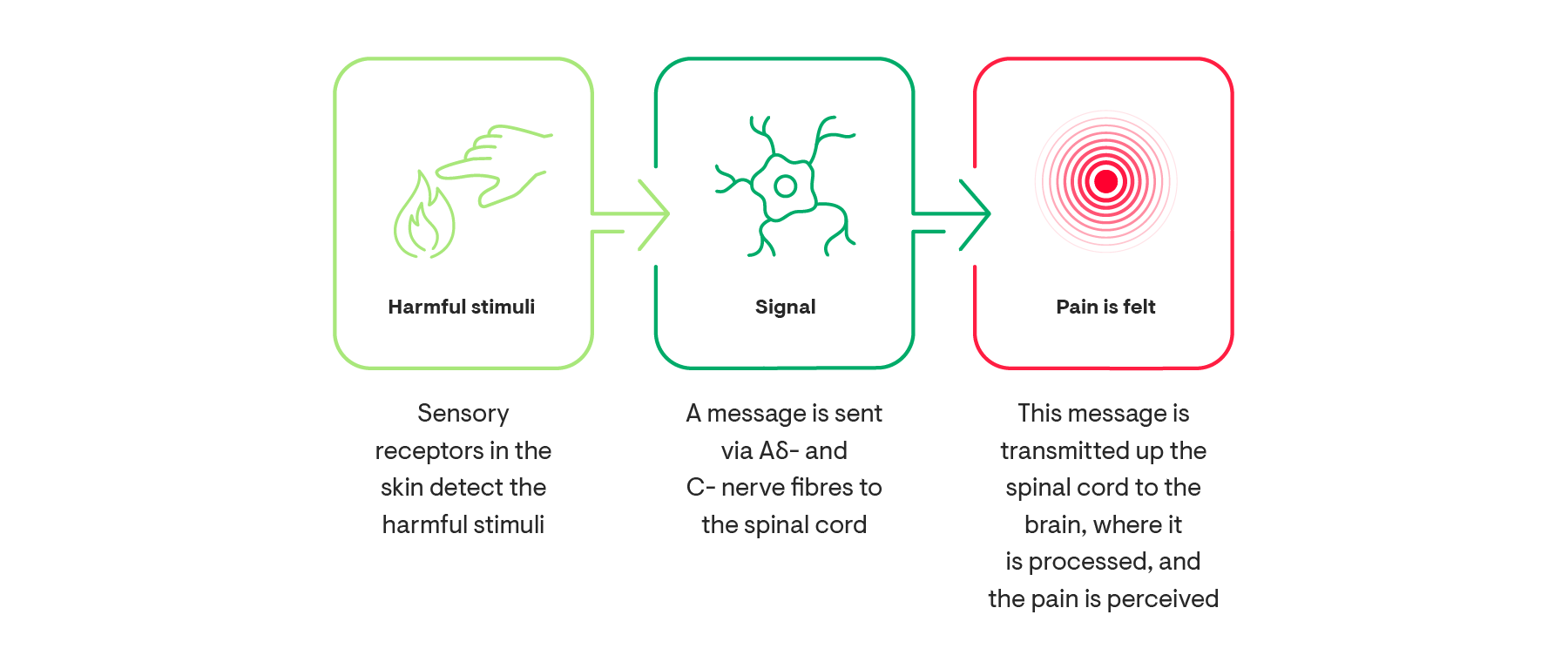

The fundamentals of pain

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.1 Pain has many dimensions and can vary in intensity, location in the body and duration of time. Depending on the type of pain, it can feel like throbbing, burning, shooting or tingling and can range in intensity from mild to severe.3,4 In addition to the physical impact, it can also have psychological, emotional and social effects on everyday life.3

Sometimes the cause of pain is obvious, such as from injury, and other times the source might come from an underlying condition. In some cases, it can be difficult to categorise the exact cause of pain.3

There are three different mechanisms that can lead to the perception of pain. In some cases, more than one mechanism may be involved.

1. Nociceptive pain

This type of pain is typically caused by damage to the body’s tissues from either injury or inflammation. Examples include:5,7,8

- Sports injury

- Arthritis

- Appendicitis

2. Neuropathic pain

This type of pain is typically caused by damage to nerves. This damage can be due to lesions in the nervous system, diseases that affect the nerves or injury. Examples include:3,5,9

- Peripheral neuropathic pain e.g., painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, chemotherapy-induced neuropathy

- Post-stroke pain

- Spinal cord injury

- Cancer-induced neuropathic pain

3. Nociplastic pain

This type of pain occurs without clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage or lesions and diseases of the nervous system. Examples include:10

- Fibromyalgia

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Non-specific back pain

What is the difference between acute and chronic pain?

Pain is complex and is not only classified by the mechanisms above, but also by severity, location in the body and duration.2 One of the most common ways to classify pain is by the duration of time someone has been experiencing pain:

| Acute Pain | Chronic Pain |

| Lasts for less than 3 months11 | Lasts for longer than 3 months12 |

| Occurs usually in response to tissue trauma and related inflammatory processes13 |

Can be due to an underlying disease such as cancer or arthritis3

OR Has no obvious cause5 or may continue after the original injury has healed3 |

| Serves a useful and life sustaining (protective) function14 | Typically serves no adaptive purpose5 |

| Poorly controlled acute pain can be a factor leading towards chronic pain15 |

Influenced by a number of interconnected factors, including:13 Biological: genetics, age, sex, sleep, hormones and internal pain regulation systems Psychological: poor sleep, anxiety or depression Sociocultural: low educational attainment, culture and poor social support |

In 2019 the IASP and the World Health Organization recognized chronic pain as a health condition in its own right13

Some of the most common types of chronic pain are:16

- Migraine

- Low back pain or lumbar pain

- Neck pain

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Pain associated with osteoarthritis

Who is affected by chronic pain?

Chronic pain is an enormous global health problem17 and affects around 1 in 5 adults worldwide.18,19,20

What are some factors that can increase the likelihood of experiencing chronic pain?13,21,22,23

Women are more likely to report or experience chronic pain than men22 and report a higher level of pain intensity and higher pain-related disability than men23

Pain is a dynamic consequence of a host of biological, psychological, and social factors; hence, guidelines have recommended interdisciplinary treatment, which ideally makes use of a personalised approach with a shared decision-making.13

The serious impact of chronic pain

Chronic pain exerts an enormous personal and economic burden, and it is considered to be one of the main causes of disability:13,19

Up to 90% of adults with chronic pain experience clinically significant insomnia24

of patients with chronic pain are less able or unable to do household chores25

of chronic pain patients have difficulty maintaining an independent lifestyle25

of patients with chronic pain have relationship difficulties25

Mental Wellbeing:

Chronic pain can have a significant impact on mental health and wellbeing.13 Research has shown that more than 50% of patients with chronic low back pain have depression and anxiety,26 and people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain with both depression and anxiety are likely to experience more severe pain and pain-related disability.27

The Economy:

The cost of chronic pain is significant:13,19,28,29

Chronic pain affects 1 in 3 Americans, costing up to $635 billion per year28

Across Europe, the cost of chronic pain is estimated to be as high as €300 billion

Chronic pain also increases the risk of other health problems and social exclusion.30

Employment:

Chronic pain affects people’s ability to do their jobs effectively.

- In the US, people with chronic pain worked 7.5 days less than those without chronic pain.31

- In the EU, more than 50% of people are prevented from doing their work because of chronic pain.32

- In the EU, chronic pain has substantial negative impacts on productivity at work.32

Having chronic pain may also affect employment. A survey revealed that less than 20% of people with chronic pain receive occupational rehabilitation in order to remain at work.32 Additionally, research in the UK found that chronic pain was present in 79% of those who were unable to work because of ill health and only in 40% of those in paid employment.33

-

References

1Raja SN, et al. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976-1982.

2Stanos S, et al. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(5):502-515.

3Orr PM, et al. Crit Care Nurs Clin N Am. 2017;29:407–418.

4Fink R. Bayl Univ Med Proc. 2000;13(3):236–239.

5National Pharmaceutical Council. Pain: Current Understanding of Assessment, Management, and Treatments. 2001. Available at: https://www.npcnow.org/sites/default/files/media/Pain-Current-Understanding-of-Assessment-Management-and-Treatments.pdf. Accessed May 2022.

6Yam MF, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2164.

7Igolnikov I, et al. Chapter 39, Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2018:423–430.

8Prescott SA and Ratte S. Chapter 23, Conn's Translational Neuroscience. 2017:517–539.

9Nicholson B. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(Suppl 9):S256–62.

10Trouvin AP and Perrot S. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(3):101415.

11World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). MG31 Acute pain. 2019. Available at: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f1404135736. Accessed May 2022.

12World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11). MG30 Chronic pain. 2019. Available at: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1581976053. Accessed May 2022.

13Cohen SP, et al. Lancet. 2021;397:2082–2097.

14European Pain Federation. What is the definition of pain? 2013. Available at: https://europeanpainfederation.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CoreCurriculumPainManagementEFIC_Version130718.pdf. Accessed May 2022.

15European Pain Federation. The Pain Management Core Curriculum for European Medical Schools. 2013. Available at: https://europeanpainfederation.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/CoreCurriculumPainManagementEFIC_Version130718.pdf. Accessed May 2022.

16Treede RD, et al. Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27.

17Goldberg DS and McGee SJ. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:770.

18Varrassi G, et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(5):1231–1245.

19Pain Alliance Europe. Survey on Chronic Pain. 2017: Diagnosis, Treatment and Impact of Pain. 2017. Available at: https://www.pae-eu.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PAE-Survey-on-Chronic-Pain-June-2017.pdf. Accessed May 2022.

20Treede RD, et al. Pain. 2015;156(6):1003–1007.

21Breivik H, et al. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1229.

22Bartley EJ and Fillingim RB. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):52–58.

23Stubbs D, et al. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(2):232–239.

24Nijs J, et al. PMR. 2020;12(4):410–419.

25Breivik H, et al. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(4):287–333.

26Oliveira DS, et al. Pain Medicine. 2019;20(4):736–746.

27Bair MJ, et al. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(8):890–897.

28U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. 2019. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf. Accessed May 2022.

29Gaskin DJ and Richard P. J Pain. 2012;13(8):715–724.

30Phillips C, et al. Health Policy. 2008;88:166–175.

31Yong RJ, et al. Pain. 2022;163(2):e328–e332.

32Pain Alliance Europe. Survey on Chronic Pain and your Work Life. A survey in 14 EU countries. 2018. Available at: PAE-Survey-2018-Pain-And-Your-Work-Life.pdf (pae-eu.eu). Accessed May 2022.

33Macfarlane G, et al. Br J Pain. 2015;9:203–212.