Chronic low back pain

(cLBP)

Many chronic conditions are challenging to manage. Here we focus on key pain conditions with a high unmet need among patients and/or healthcare professionals.

Our aim here is to provide the pain community with in-depth information about these conditions; from disease understanding to management approaches.

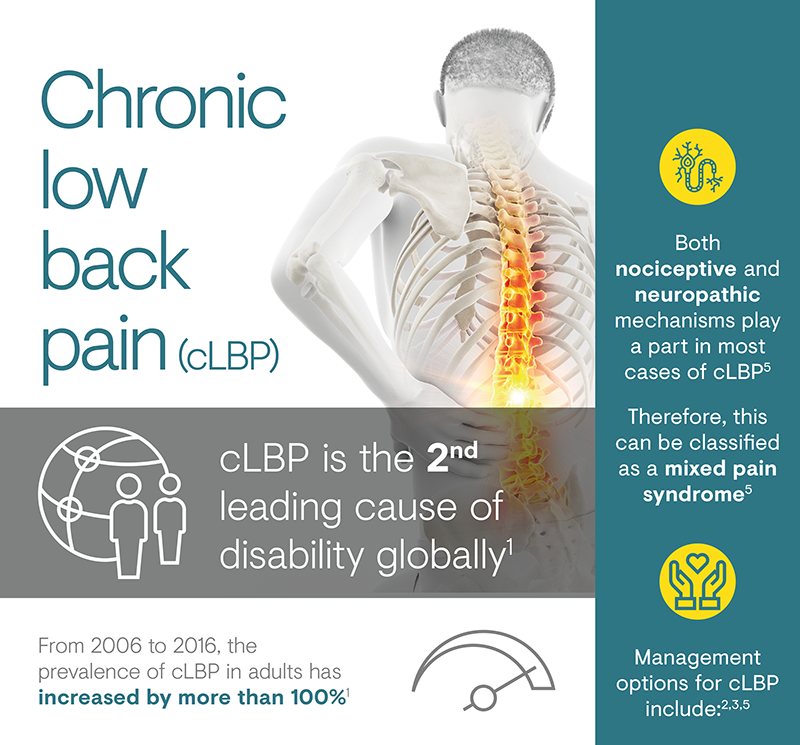

Chronic low back pain (cLBP) is defined as pain in the lumbar back region that persists for 12 weeks or longer.1 It has many different causes and often presents in a non-specific manner.1,2 cLBP represents a leading cause of disability, with a pronounced impact on quality of life, and major economic and societal consequences.2

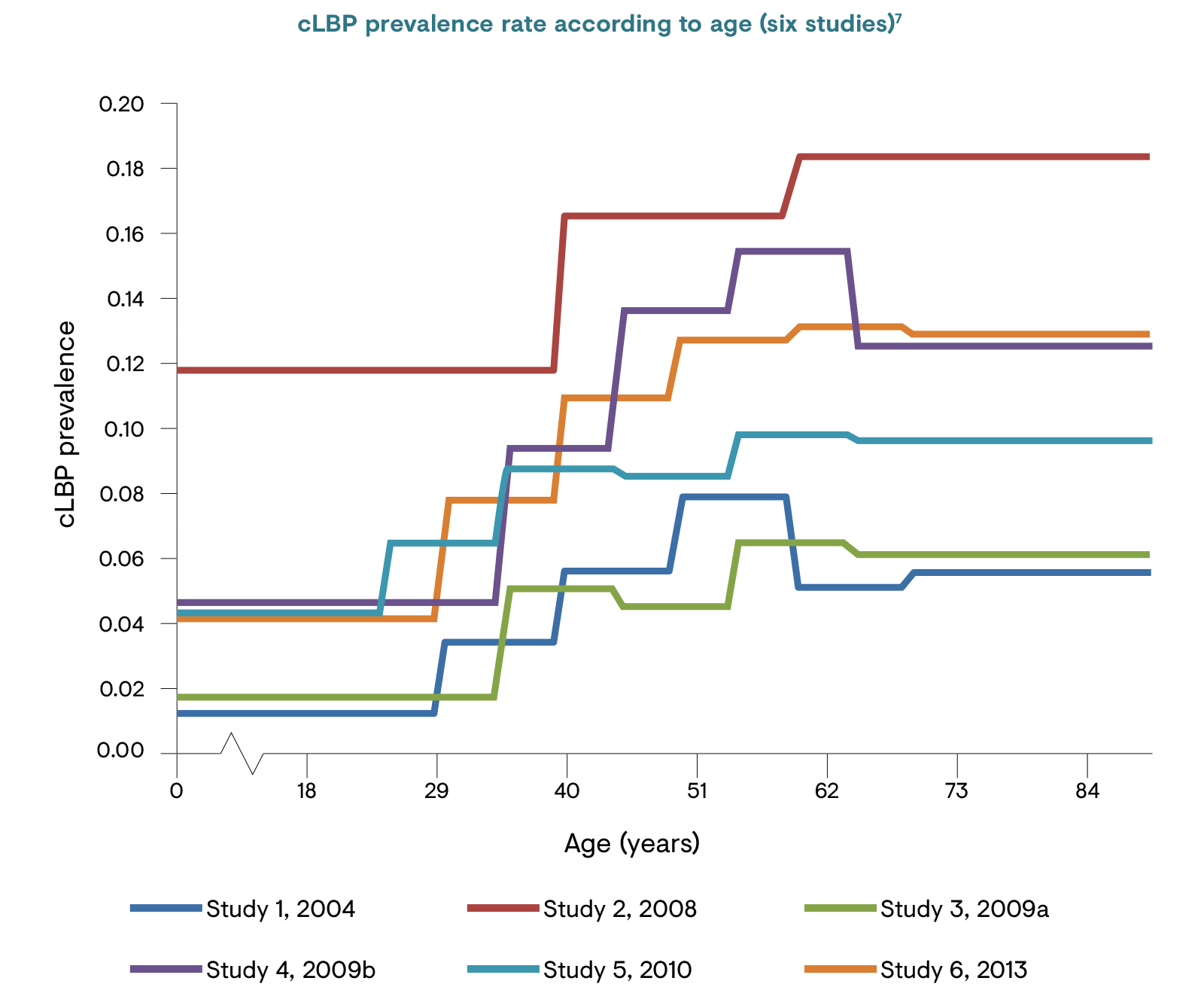

LBP represents a significant economic and social problem. From 2006 to 2016, the prevalence of both acute and chronic LBP has more than doubled.3 It is estimated that 11.9% of the global population suffers from LBP (either acute or chronic) at any point in time, rising to almost a quarter (23.2%) over any 1-month period.6 The prevalence of cLBP has been reported as 4.2% in people aged 24–39 years and 19.6% in those aged 20–59 years in two separate studies.7 Its prevalence continues to increase as the population ages, and both men and women in all ethnic groups are affected to a similar extent.3

cLBP: chronic low back pain.

cLBP: chronic low back pain.

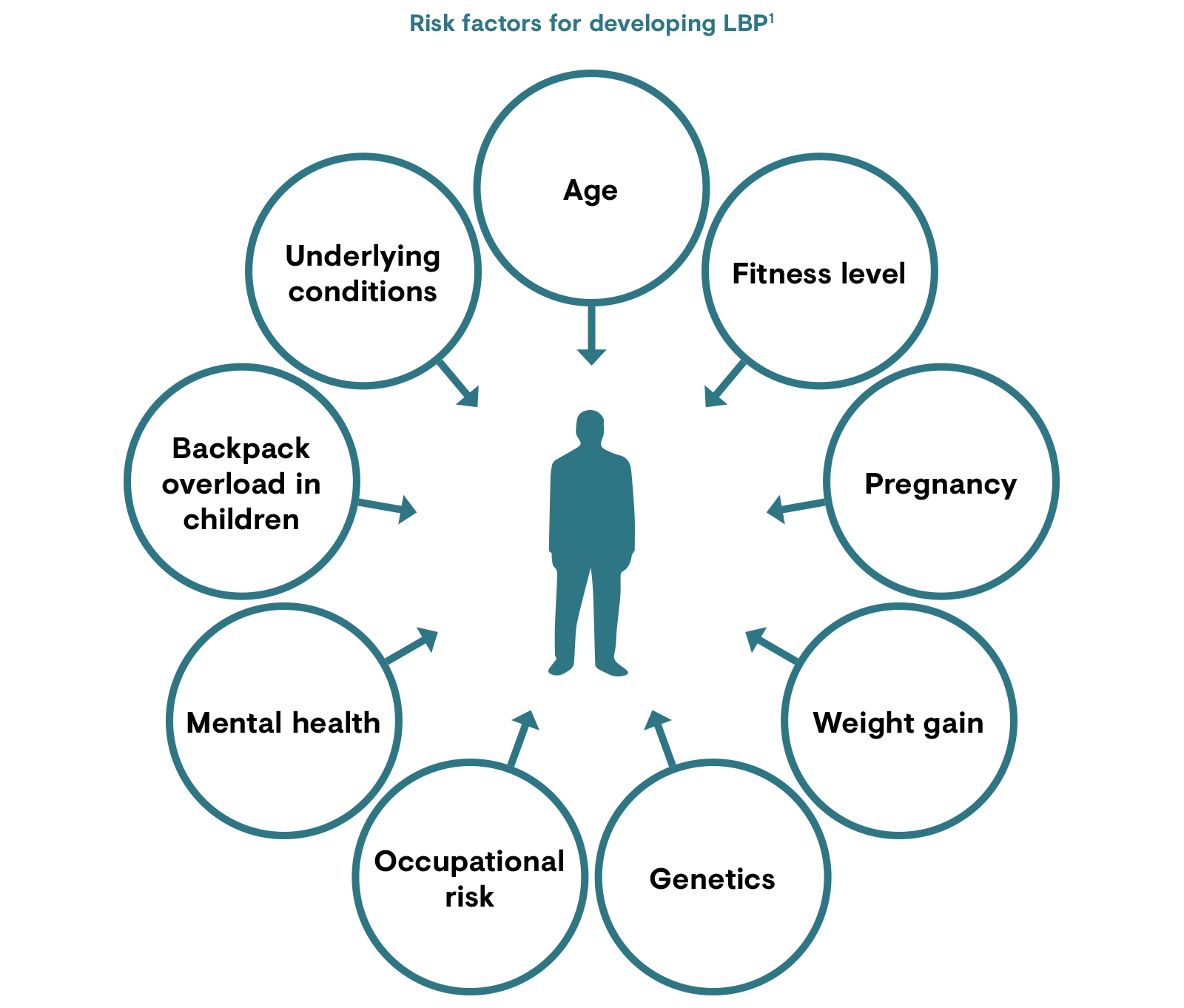

There are a multitude of potential initiating factors described for LBP. However, many are difficult to interpret because of the high prevalence of back pain in the general population.1,2 Physical factors contributing to LBP include physical status, heavy lifting and, rarely, underlying conditions such as infections, tumours or kidney stones.1 Strong psychological factors also play a role in the development of back pain.2

LBP: low back pain.

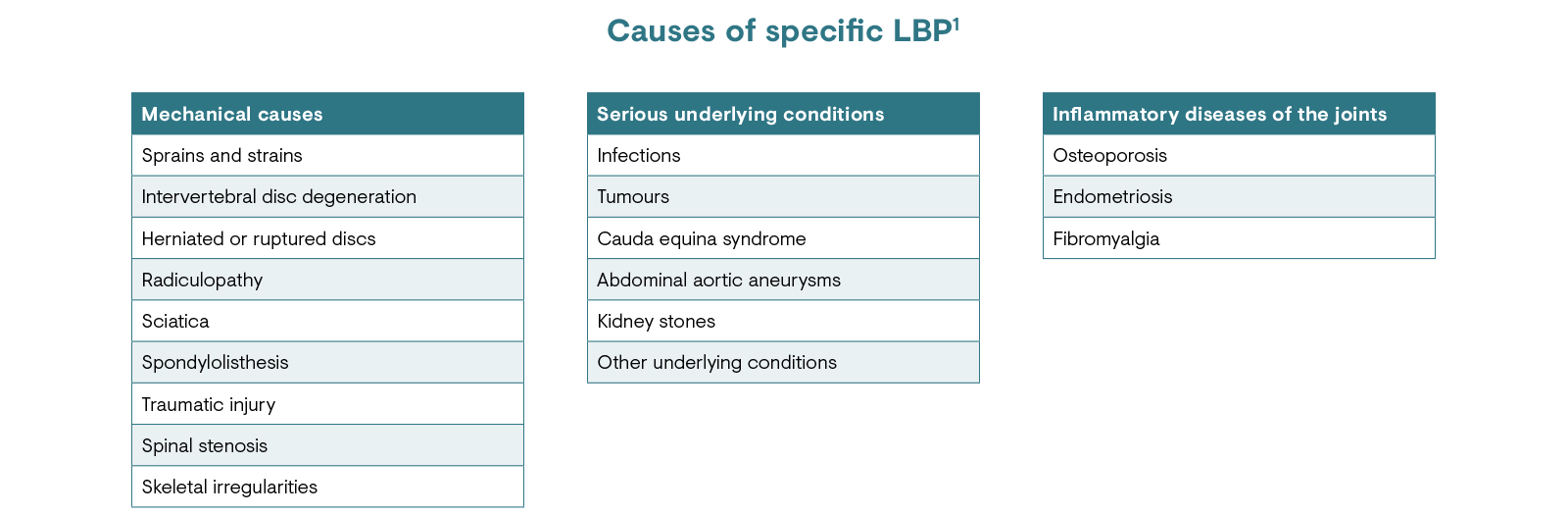

LBP represents a functional disorder that, in many cases, involves general degeneration of the spine associated with normal wear and damage as people age.1 Often, the exact aetiology of back pain remains unclear, leading to the majority of cases being labelled as ‘non-specific’.1,2 In cases where causes of back pain can be determined, they are mostly mechanical in nature, although these can also be a result of underlying conditions.1

LBP: low back pain.

Traumatic or degenerative conditions of the spine are the most common causes of cLBP.1 Symptoms may include dull aching pain, sharp pain, tingling or burning, weakness of the legs or feet. The pain may be mild or it can be so severe that surgery is warranted, and flexibility may be lost permanently.1

Comorbidities associated with cLBP include a higher frequency of musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain conditions, sleep disturbance and mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression.8 Psychological factors play an important role in a patient’s ability to retain employment, and the financial burden on healthcare systems is enormous.2

cLBP: chronic low back pain.

While cLBP often arises from a mechanical cause, neuropathic mechanisms play a part in most cases.1,5 Therefore, cLBP can be classified as a mixed pain syndrome.5

Studies have demonstrated that a large proportion of patients (20–55%) with cLBP have a higher than 90% likelihood of a neuropathic pain component, which is also suspected in a further 28% of patients.5 Such presence of a neuropathic pain component is associated with more severe pain symptoms and higher healthcare costs.5

Back pain starts as acute pain and, aside from the initial cause, peripheral/central sensitisation contributes to the progression of acute to chronic pain.3 Depending on when a patient presents to a physician, back pain may be diagnosed as acute or chronic. A complete medical history and physical examination will be conducted to identify any serious conditions causing LBP, and imaging – while not usually warranted – may be utilised to rule out specific causes of pain such as tumours and spinal stenosis.1 Despite the various tests and examinations carried out, it is difficult to ascertain the exact cause of cLBP.

LBP: low back pain.

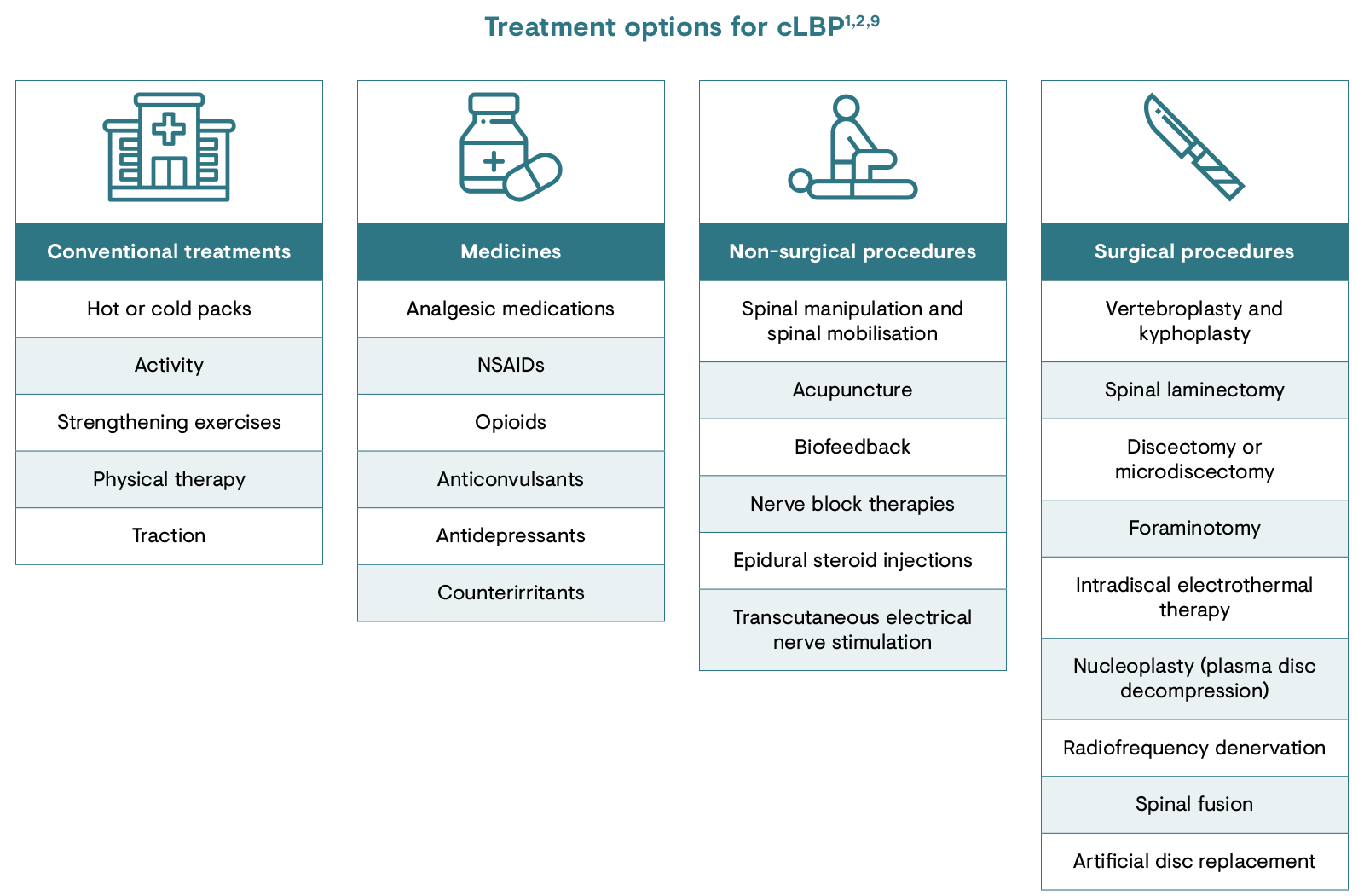

A range of strategies can be used to manage cLBP. These include non-pharmacological and pharmacological as well as surgical treatments.1,2,9 Current treatment guidelines and recommendations include non-pharmacological management, such as hot or cold packs, physical activity to strengthen muscles and medications.1 Acute pain is often temporarily relieved by drugs, though this may not be sufficient to achieve sustained pain relief in the case of cLBP.2 Commonly used medications include non-opioid analgesics, such as paracetamol/acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or opioids.2

The latest European Pain Federation position papers are available here: https://europeanpainfederation.eu/advocacy/position-papers

cLBP: chronic low back pain; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

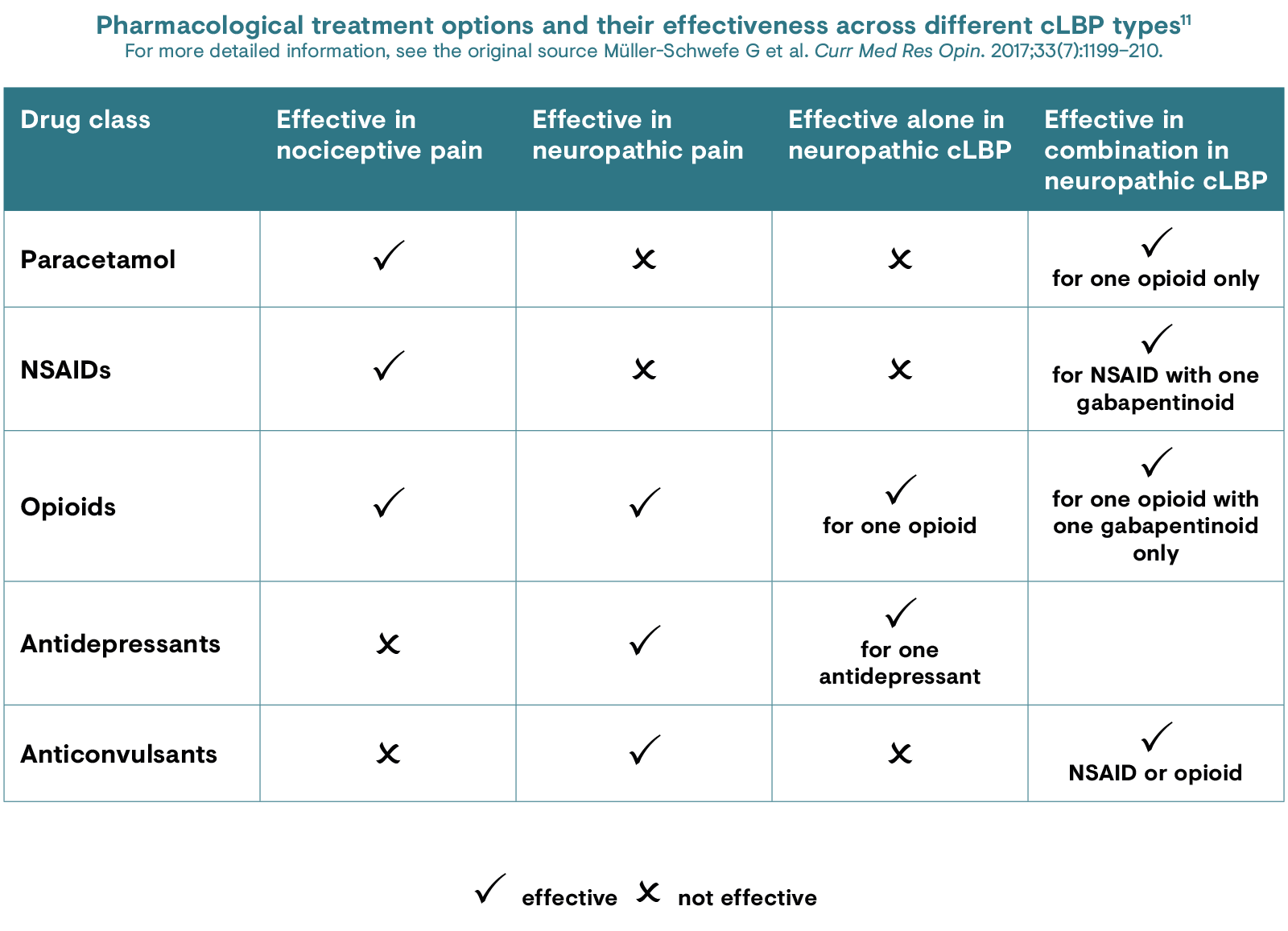

To guide the choice of treatment, clinicians should investigate the mechanisms underlying the pain.9 As the cause of cLBP can be diverse and multifactorial, and due to the specific mechanisms of action of each drug, determining the pain mechanism may allow for targeted treatment.10,11 However, identifying the pain mechanism based on patient phenotype remains a considerable clinical challenge.10

If the pain is not managed appropriately by a single speciality (e.g. a general practitioner [GP] or orthopaedist), a multimodal approach might be needed.11 Such an approach can combine a variety of modalities with complementary mechanisms of actions (e.g. two pharmacological medications with one non-pharmacological approach). Before initiating a multimodal management plan, drug–drug interactions between modalities should be considered. Depending on the patient’s presentation, different specialities may be involved in the management plan; for example, in degenerative disc disease, the interdisciplinary team might include a GP, orthopaedist, neurosurgeon, physical therapist, pain specialist and others. The importance of utilising an interdisciplinary approach has been demonstrated in cLBP; in Denmark, the rate of lumbar disc surgeries was significantly reduced following the implementation of multidisciplinary non-surgical spine clinics, which involved rheumatologists, physical therapists, GPs, chiropractors, nurses, social workers and occupational therapists.12

[Modified from Müller-Schwefe et al. 2017.11]

cLBP: chronic low back pain;

NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

A major unmet need for patients with cLBP is attaining knowledge of the source of pain; patients have a need to know the reason behind their pain and physicians require a clear diagnosis in order to effectively guide treatment. Recent guidelines state that clinicians who see patients with cLBP should explore the mechanisms that underlie the acute/chronic pain.9 This would allow for the use of more tailored therapy to optimise outcomes for the patient and avoid the generalised diagnosis of LBP that may lead to poor treatment. However, the large number of possible physical and non-physical causes of cLBP makes this difficult. In some instances of cLBP, multiple pain generators can work together; in such cases, multidisciplinary diagnosis and multimodal treatment options can be of use.5,13

1. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Low back pain fact sheet. 2020. Available at: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/low_back_pain_20-ns-5161_march_2020_508c.pdf. Accessed June 2021.

2. Ehrlich GE. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:671–6.

3. Allegri M et al. F1000Res. 2016;5:1530.

4. Maetzel A & Li L. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:23–30.

5. Morlion B. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:11–33.

6. Hoy D et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2028–37.

7. Meucci RD et al. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:1.

8. Gore M et al. Spine. 2012;37:E668–77.

9. Oliveira CB et al. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:2791–803.

10. Vardeh D et al. J Pain. 2016;17(Suppl 9):T50–69.

11. Müller-Schwefe G et al. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:481–8.

12. Rasmussen C et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(21):2469–73.

13. Varrassi G et al. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1231–45.