Chronic Post-Surgical

Pain

Many chronic conditions are challenging to manage. Here we focus on key pain conditions with a high unmet need among patients and/or healthcare professionals.

Our aim here is to provide the pain community with in-depth information about these conditions; from disease understanding to management approaches.

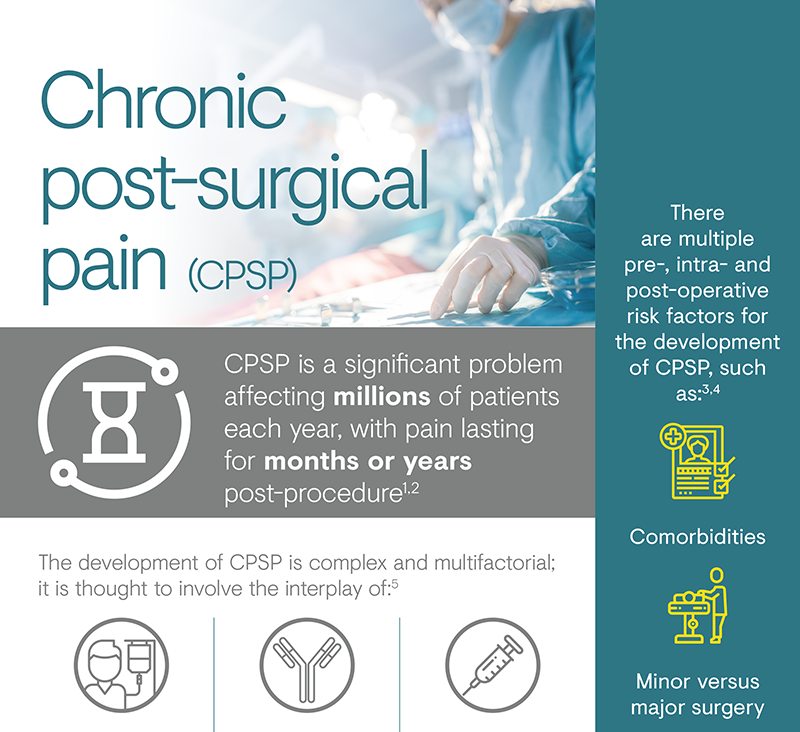

Chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) is a poorly recognised potential outcome of surgery, which can result in potentially devastating outcomes for the individual affected.1 The 11th edition of International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-11 definition of CPSP is pain that develops or increases in intensity after a surgical injury and persists beyond the healing process (i.e. at least 3 months after the initiating event), which is localised to the surgical field or projected innervation territory of a nerve within this area.2 Nerve injury caused during a surgical procedure has been implicated in the development of CPSP, with many patients experiencing neuropathic pain.2 CPSP can represent a severe complication for patients, leading to functional limitation and psychological trauma, as well as being a problem for the operative team in the form of feelings of frustration and disappointment.3

Surgery is recognised as one of the most frequent causes of chronic pain in patients attending pain clinics.9 It is estimated that acute post-surgical pain will persist in 10–50% of cases following common surgical operations.10 Therefore, CPSP affects millions of patients every year, with pain lasting from months to years, resulting in widespread patient suffering and ensuing economic consequences.1 The prevalence of CPSP varies by type of surgery; the operations with the highest incidence of CPSP are amputation, thoracotomy and breast surgery.1 In a large European trial observing self-reported pain scores, moderate to severe neuropathic pain was shown to occur 35–57% of post-surgical patients.8

The light blue portion of each bar represents the incidence range of chronic pain for that type of surgery.

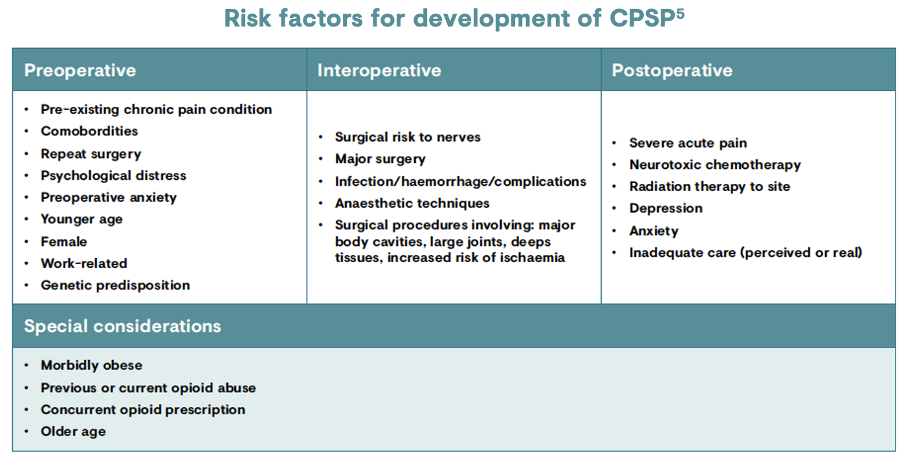

Several risk factors have been identified for the development of CPSP, and there is no single dominant factor.4 The risk determinants can be classified according to the timing of the surgery, with factors prior to, during and after the operation contributing to the risk of developing CPSP.6

One of the leading risk factors for CPSP is the extent of tissue damage during surgery and injury to the nerves during dissection or retraction.4 Nerves are at continuous risk of contusion, stretching, division or entrapment from insults such as surgical retraction, diathermy or compression with bones.4 It may be possible to reduce the risk by giving consideration to the surgical approach, pain management and psychological predisposition.9 Psychological risk factors are another important consideration; negative affective constructs such as anxiety, depression, pain catastrophisation and general psychological distress have been consistently identified as risk factors for CPSP.11

PAIN OUT, an international quality improvement and research network, is conducting research into peri-operative pain management in the clinical routine setting utilising a large registry.12 Recent data from the project suggest that educational interventions may improve processes.12

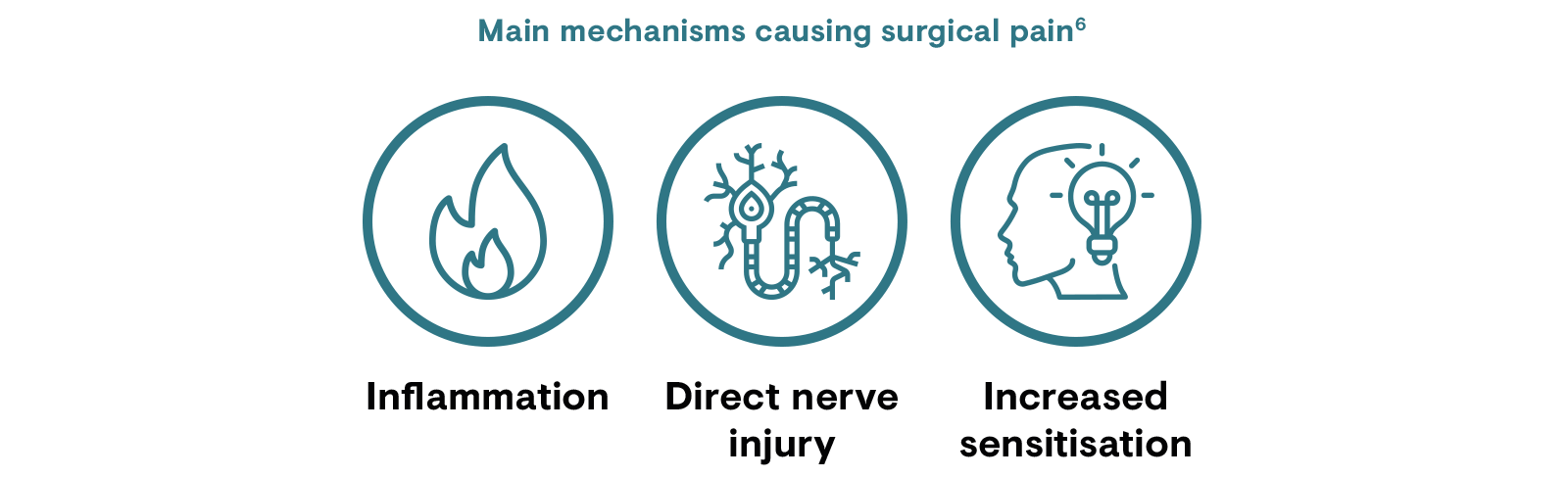

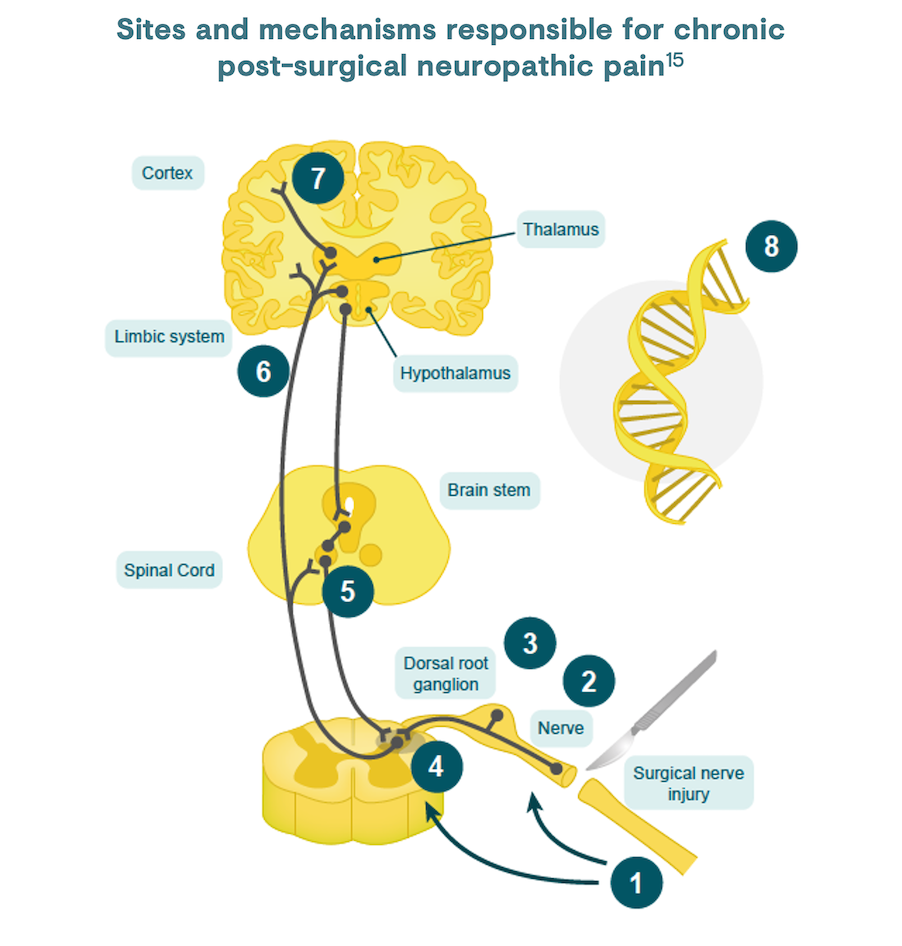

Neuroplasticity (spinal sensitisation) following trauma may transform acute pain to chronic pain if not treated in a timely manner.4 However, the development of CPSP is thought to be multifactorial, involving the interplay of patient factors (e.g. psychology, genetics, pre-existing pain); the inflammatory response to tissue damage; and the surgical, anaesthetic and analgesic techniques applied.8

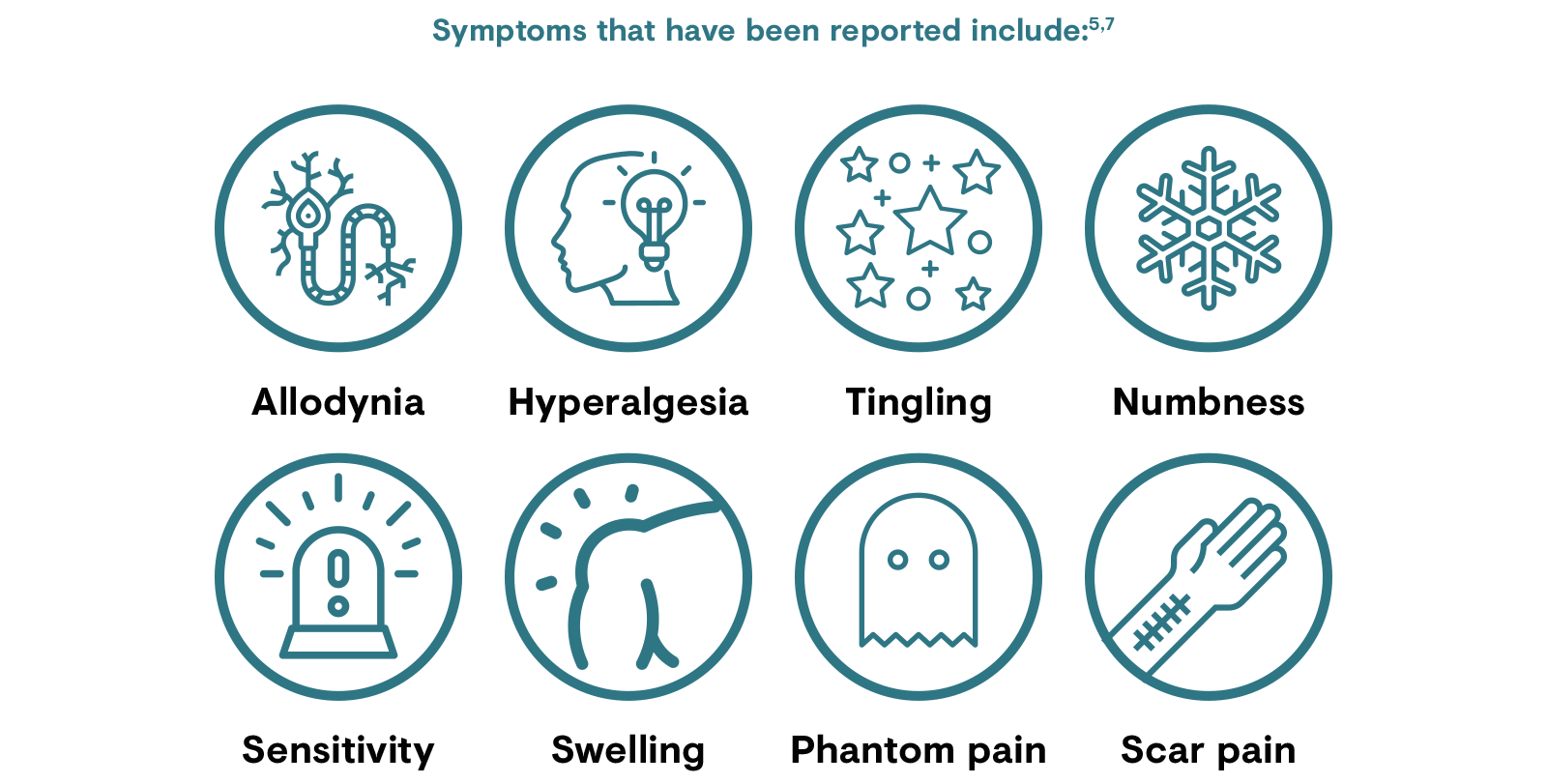

The signs and symptoms of peri- and post-surgical pain can be diverse because of the highly heterogeneous population and also because the amount of tissue injury and degree of inflammation varies widely by operation type and procedures utilised.3 Nerve injury during surgery has been implicated in the development of CPSP and some (but not all) patients with CPSP will present with evoked and spontaneous symptoms associated with neuropathic pain, such as allodynia and hyperalgesia.6 However, any link between nerve damage during surgery and the development of CPSP is complicated. Not all patients with nerve damage develop CPSP, and those who do develop CPSP do not necessarily have neuropathic pain.6Neuropathic pain is associated with greater pain intensity and functional impairment compared to those with non-neuropathic post-surgical pain, and negatively impacts quality of life.8,14

Inflammatory and immune reactions after nerve damage to axons results in the release of neurotransmitters that act locally and in the spinal cord to produce hypersensitivity and ectopic neural activity; this contributes to central sensitisation.6,15 Central sensitisation occurs when repetitive nociceptive stimuli result in altered dorsal horn activity and amplification of sensory flow. This can lead to persistent nervous system changes, for example, death of inhibitory neurons, their replacement with excitatory afferent neurons, and microglial activation. These changes lead to post-surgical neuropathic pain symptoms.6

According to the ICD-11, CPSP is defined as pain that develops in intensity after a surgical procedure and persists beyond the healing process, at least 3 months after the initiating event.2 The pain must be localised to the surgical field or area of injury, projected to the innervation territory of a nerve situated in this area or referred to a dermatome or Head’s zone (regions of altered sensation on the skin, at relevant spinal cord segments, after injury/surgery).2 Other causes for the pain and the possibility that it might be continuing from the pre-existing problem must be excluded.2,16

Specific subdiagnoses included in the ICD-11 are chronic pain after amputation, spinal surgery, thoracotomy, breast surgery, herniotomy, hysterectomy, and after arthroplasty.2

Click here to view the IASP/EFIC fact sheet on current management of post-surgical pain in adults.

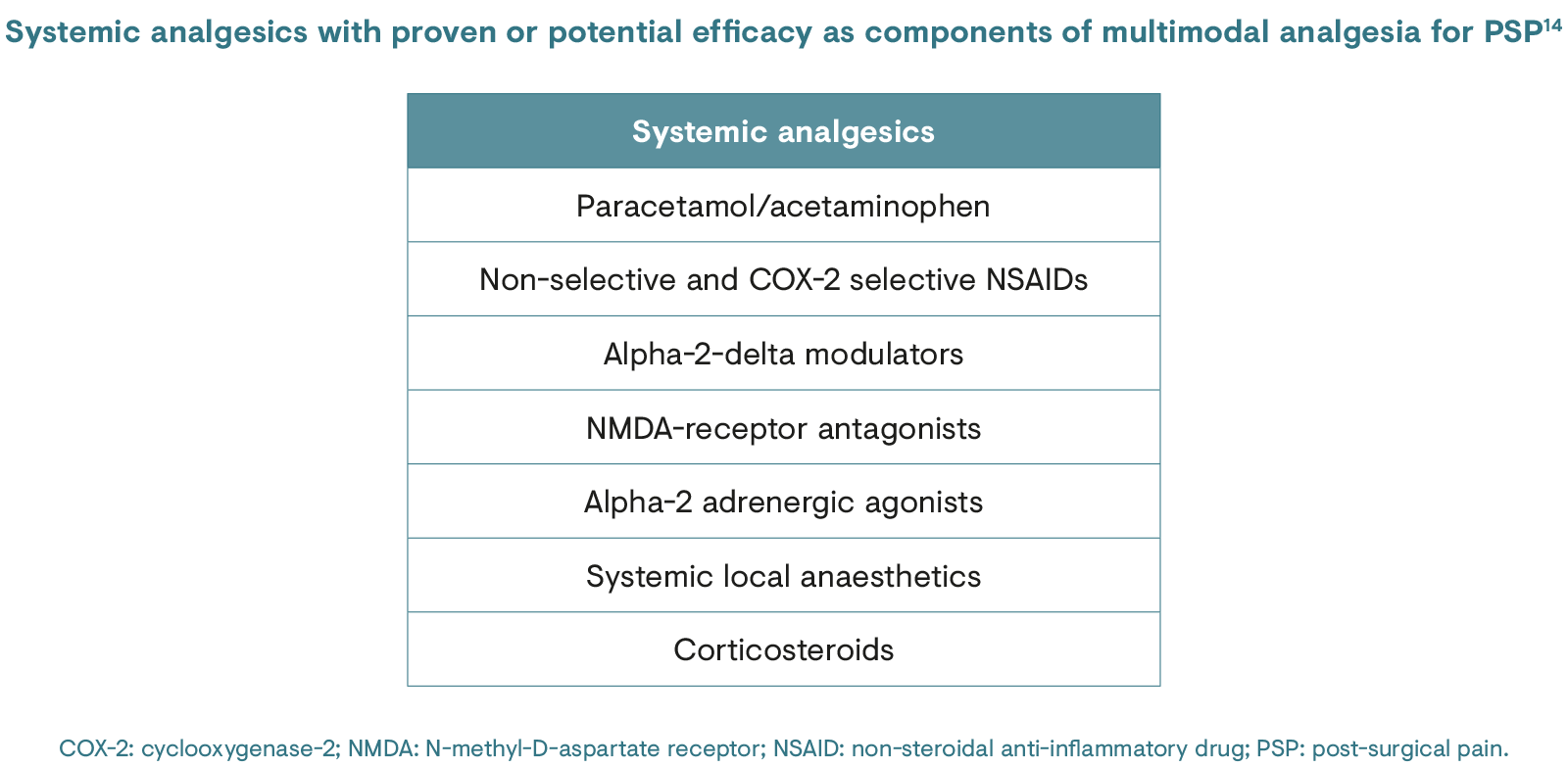

CPSP is a significant clinical problem that seriously impacts post-operative rehabilitation and health-related quality of life. Despite increased research on the pathophysiology of CPSP and recent advances in analgesic therapies, many patients still report severe CPSP.16 An improved understanding of the pathophysiological processes causing the transition from acute to chronic pain is vital to expand the current multimodal approach to include preventive treatments for CPSP.17 The same holds true for treatment of CPSP once it becomes established; management can be inadequate and a greater understanding of how best to both prevent and treat this condition is therefore needed.18

1. Gregory P & Settles K. Pract Pain Manag. 2013;13(9):1–6.

2. Correl D. F1000Res. 2017;6:1054.

3. Werner MU & Kongsgaard UE. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113(1):1–4.

4. Thapa P & Euasobhon P. Korean J Pain. 2018;31:155–73.

5. Macrae WA. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:77–86.

6. Richards A. Management of chronic post-surgical pain: an overview. In: Australian Medical Student Journal. 2017. Available at: https://www.amsj.org/archives/6110. Accessed June 2020.

7. Searle RD & Simpson KH. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2010;10:12–14.

8. Bruce J & Quinlan J. Rev Pain. 2011;5:23–9.

9. Reddi D & Curran N. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:222–7.

10. Schug SA et al. Pain. 2019;160(1):45–52.

11. Weinrib AZ et al. Br J Pain. 2017;11(4):169–77.

12. Zaslansky R et al. Pain Rep. 2019;4(1):e705.

13. Kehlet H et al. Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1618–25.

14. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and European Pain Federation (EFIC). Factsheet: Management of postsurgical pain in adults. 2017. Available at: https://www.europeanpainfederation.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/05.-Management-of-Postsurgical-Pain-Management.pdf. Accessed June 2020.

15. Clauw DJ, Essex MN, Pitman V, Jones KD. Reframing chronic pain as a disease, not a symptom: Rationale and implications for pain management. Postgrad Med 2019; 131: 185–98.

16. Richebé P et al. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:590–607.

17. Van de Ven TJ & Hsia HLJ. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:366–71.

18. Kleiman AM et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42(6):698–708.