Fibromyalgia

Many chronic conditions are challenging to manage. Here we focus on key pain conditions with a high unmet need among patients and/or healthcare professionals.

Our aim here is to provide the pain community with in-depth information about these conditions; from disease understanding to management approaches.

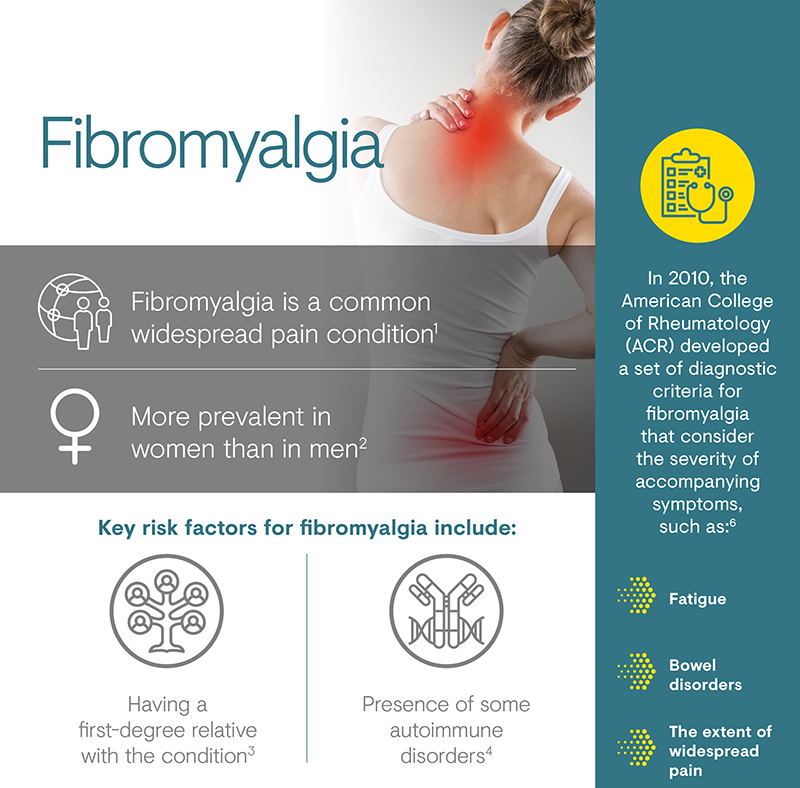

Fibromyalgia is characterised by chronic widespread pain and joint stiffness, as well as systemic symptoms manifesting as mood disorders, fatigue, cognitive dysfunction and insomnia.1,2 It does not have a well-defined underlying cause; however, it can be associated with rheumatoid disease, psychological disorders, infections and diabetes.1

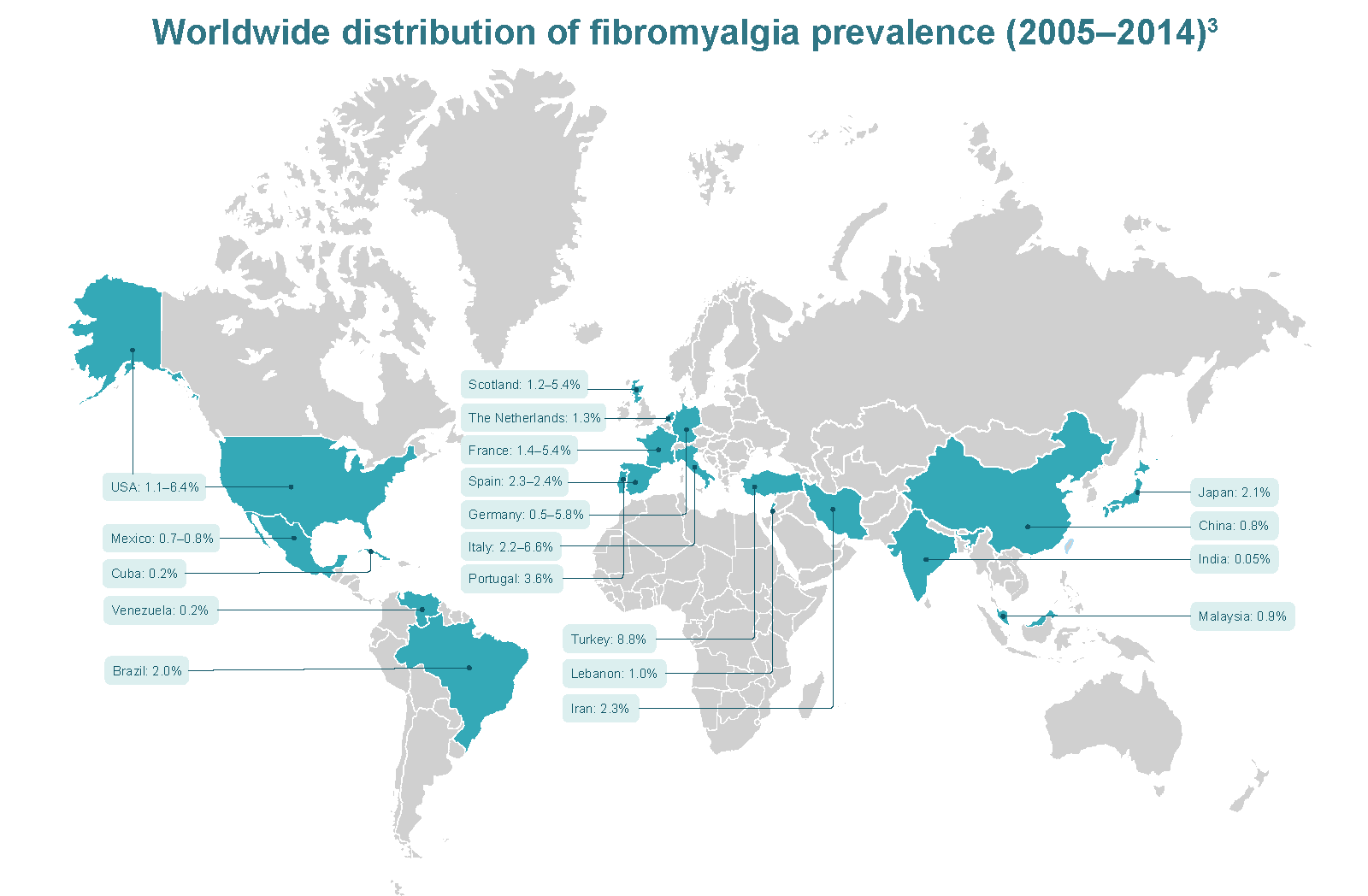

Fibromyalgia is one of the most common chronic pain conditions,

present in as much as 2–8% of the population,2 though a

more recent literature review suggests a slightly lower prevalence of

between 0.2% and 6.6%, with a higher prevalence in women of 2.4–6.8%

than men.3 Prevalence estimates tend to be higher in

Europe and the United States, compared with South America and East

Asia.3

While 75–90% of sufferers are women,

it also occurs in men and children of all ethnic groups.9–11

Socio-economic factors are also believed to influence the prevalence

of fibromyalgia, with estimates of 0.69–11.4% in urban areas compared

with 0.06–5.2% in rural areas.3

Adapted from Marques et al. 2017.3

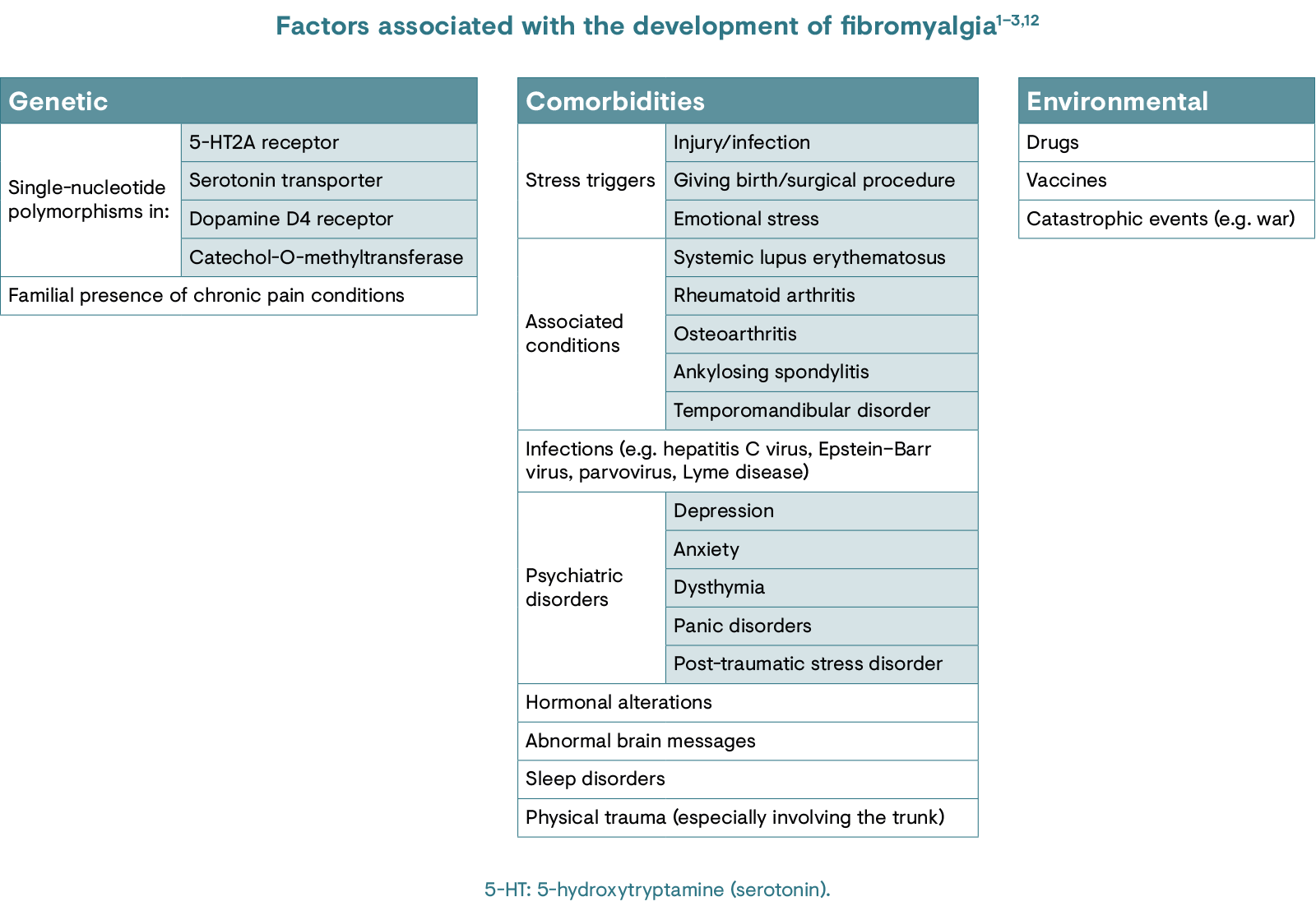

There is strong familial component associated with fibromyalgia; people with first-degree relatives who suffer from fibromyalgia have an 8-fold greater risk of developing the condition compared with the general population.5 Autoimmune disease is another well-documented risk factor for fibromyalgia; up to 65% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and 57% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have the condition.6 Twin studies indicate that the risk of developing fibromyalgia is evenly distributed between environmental and genetic risk factors.2

While there is a multitude of risk factors, the exact cause of fibromyalgia is unknown.12 It is thought to predominantly arise as a result of CNS dysregulation.1 The neuroendocrine and autonomic nervous systems have also been implicated, with a particular emphasis on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the stress hormone, cortisol.1 Other key factors thought to contribute to the development of fibromyalgia include possession of genes associated with nervous system dysfunction, stress at home or work, or a history of a traumatic event or experience.13

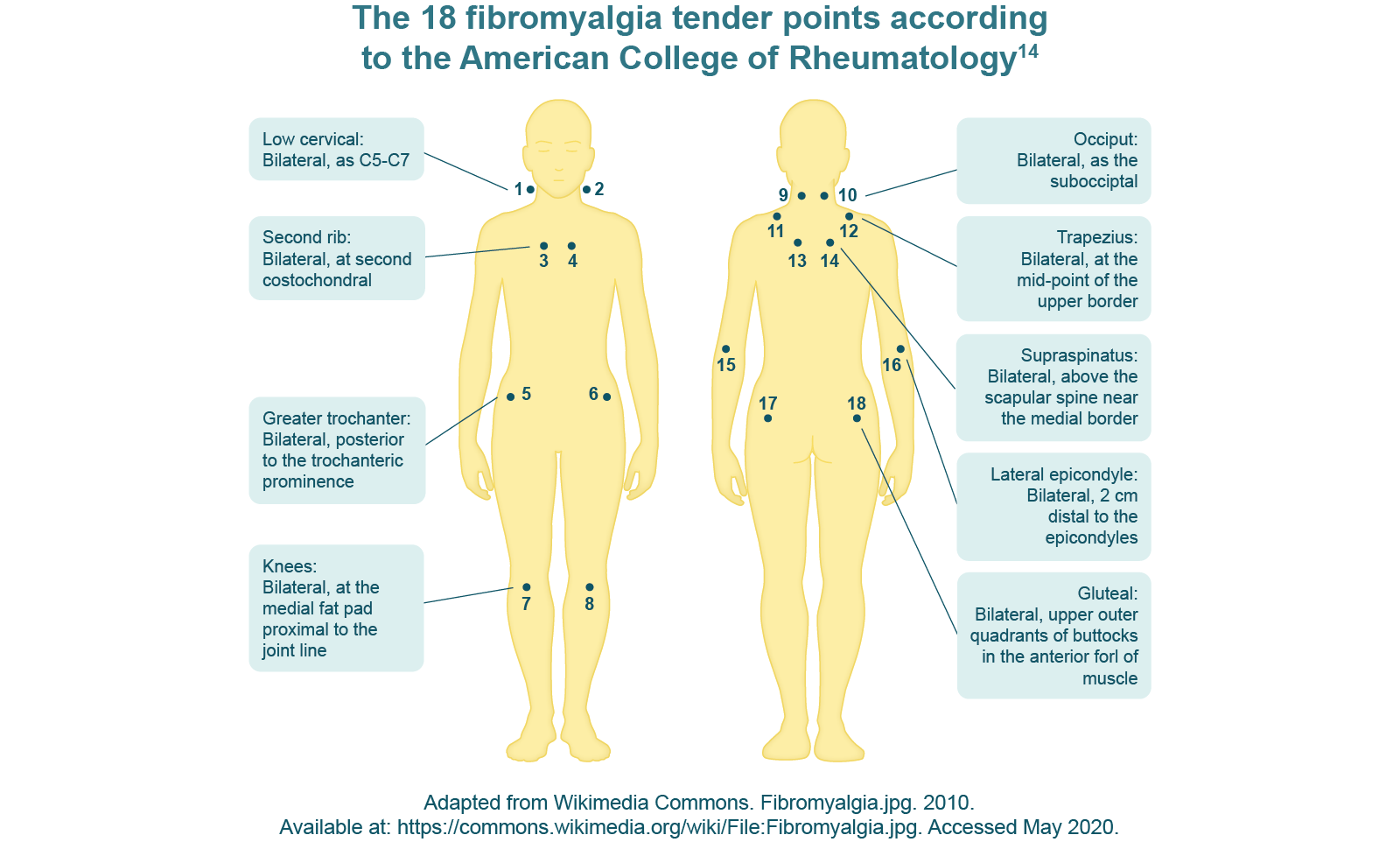

Musculoskeletal pain is the main feature of fibromyalgia.5 Patients present with distinct diffuse, multifocal pain that waxes and wanes.5 Along with deep muscle pain, people with fibromyalgia experience pain on light touch. In particular, 18 regions of extreme tenderness (or ‘tender points’) have been identified as characteristic of fibromyalgia (see Diagnosis section.)1,5 Other frequent symptoms include headaches, sleep disorders, fatigue, cognitive problems, irritable bowel and mood problems, and joint stiffness.1,2,5

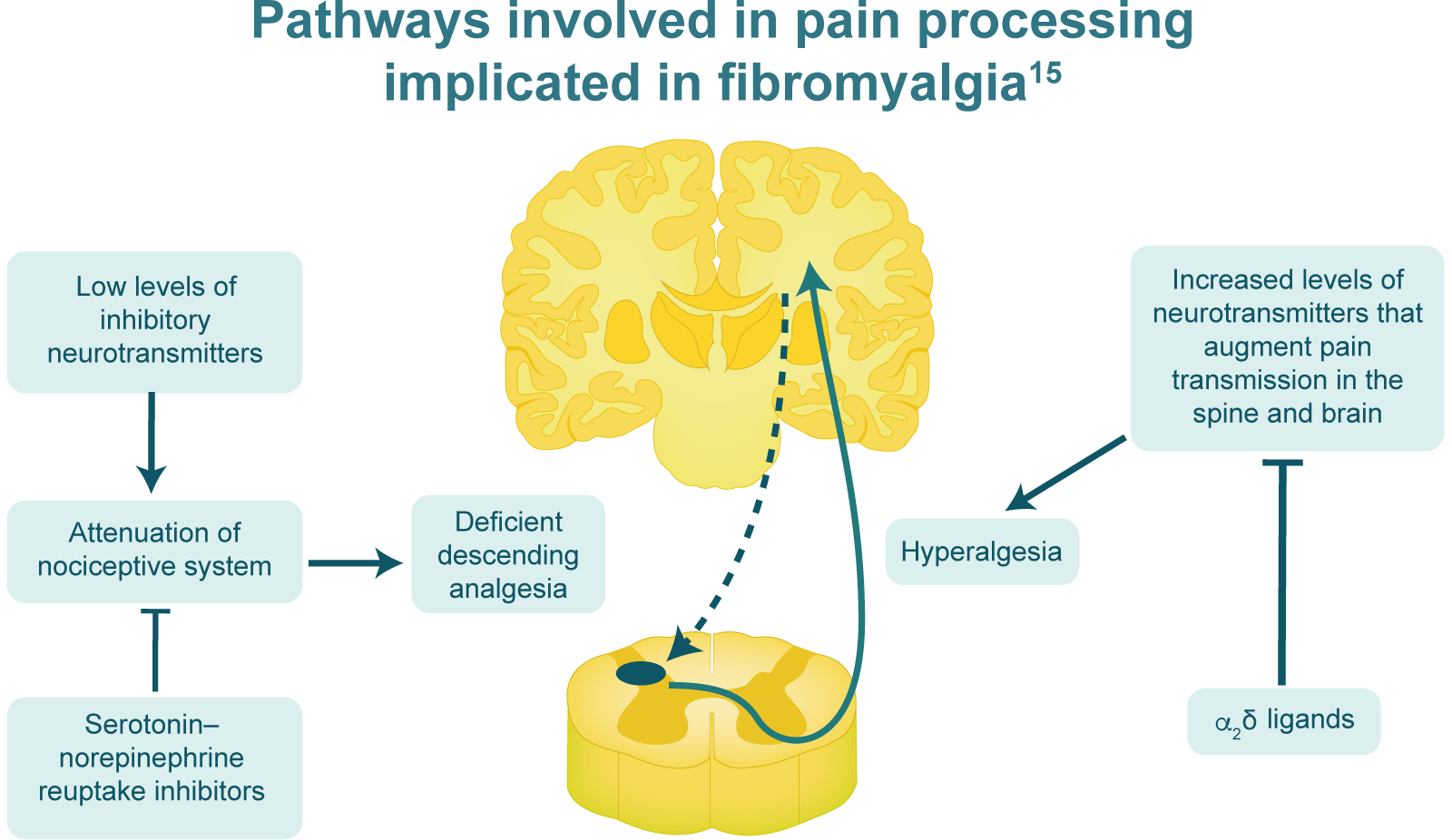

Fibromyalgia is believed to be predominantly a disorder of central pain processing, resulting in heightened responses to painful stimuli (hyperalgesia) and painful responses to non-painful stimuli (allodynia).5 Central sensitisation is considered to be the main mechanism underlying fibromyalgia and refers to an increased response to stimulation mediated by CNS signalling.1 This augmented CNS signalling can be attributed to a phenomenon coined ‘wind-up’, which describes an increased excitability of spinal cord neurons.1 The effect of this is that after a painful stimulus, subsequent stimuli of the same intensity are then perceived as stronger – this is a healthy phenomenon but in fibromyalgia patients, it occurs in excess.1,5

Descending inhibitory pain pathways that modulate responses to painful stimuli are impaired in patients with fibromyalgia, which exacerbates central sensitisation.1

Augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia is attributable to an

imbalance of several neurotransmitters that determine the ‘volume

control’ on pain processing. Low levels of inhibitory

neurotransmitters might lead to an attenuated anti-nociceptive

system, whereas serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors might

work to increase anti-nociceptive activity. Levels of

neurotransmitters that augment pain transmission, such as substance

P, glutamate/excitatory amino acids and nerve growth factor, are

increased in fibromyalgia and probably contribute to increased

activity in ascending pain transmission pathways. α2δ ligands might

be working to decrease the release of excitatory neurotransmitters.

Adapted

from Schmidt-Wilcke T & Clauw DJ. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:518–27.

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia has historically been based on the satisfaction of two main criteria, as approved by the ACR:1,16

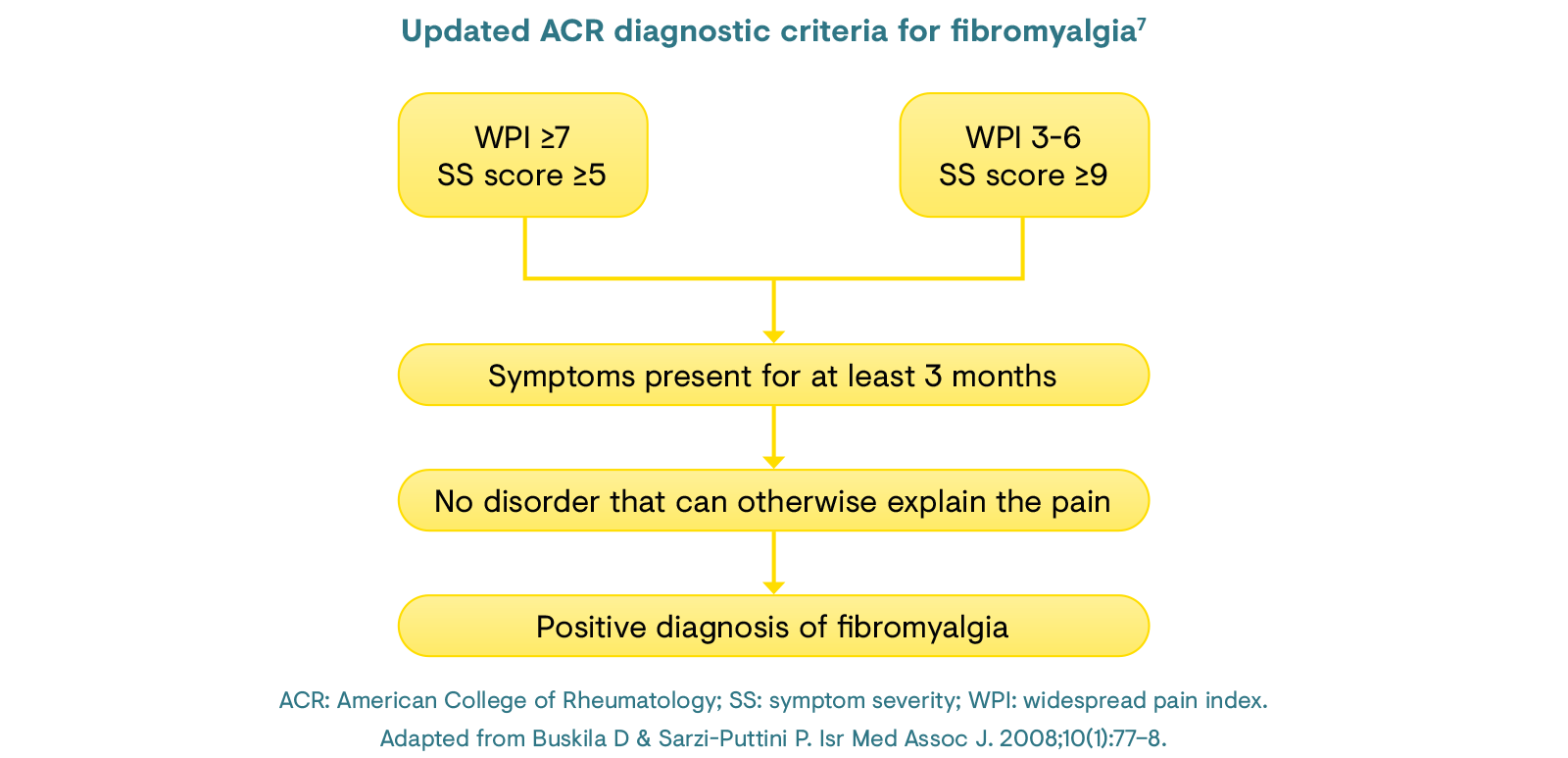

An updated diagnostic tool was developed by the ACR in 2010, which removed the need for tender point identification and considered accompanying symptoms, such as fatigue and bowel disorders.7 These criteria employ a symptom severity (SS) scale score (0–12) for symptoms including fatigue, cognitive problems and somatic symptom count, and a widespread pain index (WPI; 0, 1–3, 4–6, ≥7), which can also be utilised for monitoring patients over time.7

Nevertheless, the diagnosis of fibromyalgia remains a challenge, typically taking over 2 years and requiring almost four consultations with different physicians.17

Treatment for fibromyalgia focuses on relieving pain, increasing

sleep and improving physical function.1 As a result of

the combination of genetic and environmental causes, a multifaceted

treatment approach is needed.1 Non-pharmacological

options that are supported by some degree of evidence include

cognitive behavioural therapy, aerobic exercise, strength training,

tai chi, hydrotherapy, acupuncture and spa therapy.1,17

To date, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has not

approved any drugs for the treatment of fibromyalgia and only three

drugs are approved for use by the United States Food and Drug

Administration: duloxetine, milnacipran and pregabalin.1,18

Opioids are not recommended by any current guidelines for the

management of fibromyalgia, as biochemical and neuroimaging data

suggest that opioidergic activity is normal or increased in

fibromyalgia.1

The European League

Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends that management should take a

stepwise approach, focusing first on non-pharmacological approaches.17

In the absence of adequate relief, a pharmacological approach may be

tried, which should be individualised according to the patient, for

instance to address a mood disorder, severe pain or sleep

disturbance. However, supporting evidence for currently available

therapies is generally weak.17

View the management recommendations from EULAR here.

Within the rheumatology field, fibromyalgia is traditionally considered a ‘centralised pain syndrome’.19 However, a number of patients with fibromyalgia have been identified with comorbid small fibre neuropathy, suggesting the involvement of neuropathic mechanisms.6,19 An alternative hypothesis views fibromyalgia as a stress-related dysautonomia with neuropathic pain features.19 This would implicate dorsal root ganglia as potential autonomic-nociceptive short circuit sites and dorsal root ganglia sodium channel blockers as potential fibromyalgia analgesic medications.19

The widespread, deep pain of fibromyalgia can be a consequence of chronic psychological stress with autonomic dysregulation.20 Stress and the ischaemic pain it generates are fundamental to the multiple disorders of fibromyalgia.20 A therapeutic procedure that attenuates stress and peripheral vasoconstriction should be highly beneficial for fibromyalgia.20 Physical exercise has been shown to counteract peripheral vasoconstriction and to attenuate stress, depression, and fatigue, as well as improve mentation and sleep quality.20 Thus, exercise can interrupt the reciprocal interactions between psychological stress and each of the multiple-system disorders of fibromyalgia.20

There are currently no EMA-approved treatments for fibromyalgia; therefore, there is still a great need for targeted treatment for this chronic condition.18 Poor data generation from unrepresentative study populations in clinical trials has a major impact on drug development in this area. In addition, it is clear that fibromyalgia is a multifaceted disease that warrants the implementation of an individualised management approach, encompassing non-pharmacological and pharmacological modalities as well as comprehensive patient education, in order to address both the diverse contributory mechanisms and patients’ other comorbidities and additional needs.15

1. Bellato E et al. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:426130.

2. Clauw DJ. JAMA. 2014;311(15):1547–55.

3. Marques AP et al. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed. 2017;57(4):356–63.

4. Jahan F et al. Oman Med J. 2012;27(3):192–95.

5. Clauw DJ et al. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):S3–S13.

6. Buskila D & Sarzi-Puttini P. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10(1):77–8.

7. Graystone R et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48(5):933–40.

8. Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:600–10.

9. Branco JC et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(6):448–53.

10. Kashikar-Zuck S & Ting TV. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(2):89–96.

11. Muraleetharan D et al. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(4):952–60.

12. National Health Service. Fibromyalgia. Causes. 2019. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/fibromyalgia/causes. Accessed May 2020.

13. InformedHealth.org [Internet]. What is known about the causes of fibromyalgia? Cologne: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 2018. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK492983/?report. Accessed May 2020.

14. Wikimedia Commons. Fibromyalgia.jpg. 2010. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fibromyalgia.jpg. Accessed May 2020.

15. Schmidt-Wilcke T & Clauw DJ. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:518–27.

16. Wolfe F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–72.

17. Macfarlane GJ et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:318–28.

18. Acquadro C et al. Value Health. 2015;18:A335–766.

19. Martinez-Lavin M et al. Clin Rheum. 2018;37:3167–71.

20. Vierck CJ et al. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:951354.